Prince Monolulu: The Truth Behind Horse Racing’s Original Showman Tipster

“I gotta horse, I gotta horse to beat the favourite…”

The booming unforgettable catchphrase of Ras Prince Monolulu. A maverick tipster, he was one of the first black people to appear on British television and became an international celebrity.

Lion tamer, fire eater, street dentist, preacher, tribal chief, boxer, prisoner of war, entertainer. A CV like no other.

This remarkable figure arrived in England at the turn of the 20th Century claiming to be from Ethiopia, and died in London in 1965, at the age of 84.

But what is fact and what fiction? How is he viewed decades after the end of his extraordinary life? And did he really suffer death by chocolate?

As we will discover, all was not quite as it seemed.

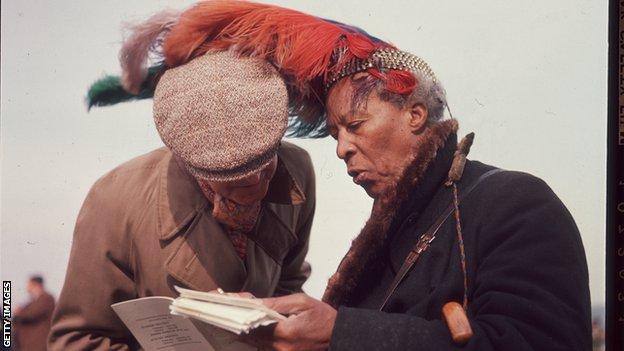

Standing tall with a headdress of ostrich feathers, lion paws swinging from his neck, in baggy pantaloons and holding a tartan umbrella, Monolulu held court before entranced crowds at racecourses across England.

“I’ve gotta horse to beat the favourite, Spion Kop will win the Derby, put your shirt on it, put your pants on it. And when you win – roast beef, two veg, Yorkshire pudding, and God save the King.”

Spion Kop won the 1920 Derby at odds of 100-6 (about 16-1) netting Monolulu a reputed £8,000 (worth around £400,000 in today’s money).

And as a rare free tip, it also brought a big following for the man with quickfire patter worthy of Muhammad Ali and a flamboyant style later echoed by racing pundit John McCririck.

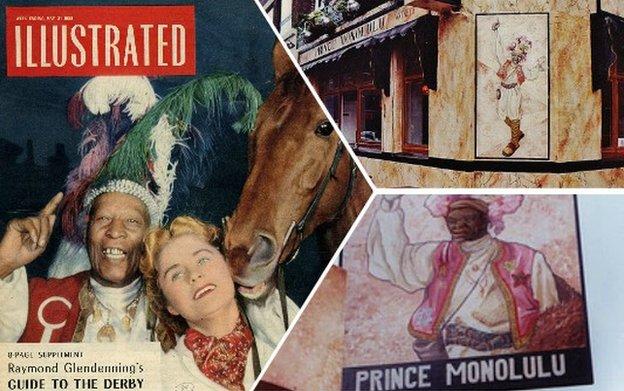

From the 1920s to the 1960s, Monolulu appeared on newsreels from major racing fixtures like Derby Day at Epsom as regularly as the Royal Family.

Punters paid for his racing tips, sealed in envelopes with the warning not to pass the selection on. He made and lost a fortune, clocked up a succession of court appearances, was married several times, and invariably left people with a smile on their face.

“When I was growing up, everybody in my family knew who he was because of his flamboyance and character,” says historian and author Stephen Bourne.

“He shouldn’t be bypassed. He should be part of British history because he was such a popular character.”

Thanks to painstaking research from retired policeman John Pearson, the truth about Monolulu’s life has taken shape.

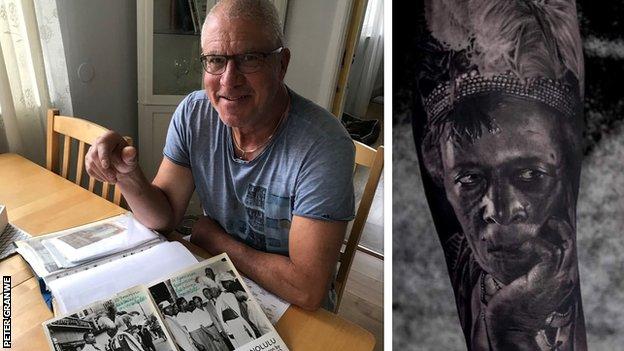

Now 84, former inspector Pearson recalls how, in his rookie days as a bobby on the beat in the 1950s, he bumped into a larger-than-life character in Buckinghamshire market town Chesham.

“I turned around and thought ‘who on earth is that?’ I got the shock of my life. I was looking straight into the eyes of what I thought was an African chief,” he remembers.

Curious, he set about discovering more and his interest turned into a serious hobby after Monolulu’s death and his own retirement.

Having appealed for more information, he was contacted by an air hostess who remembered taking Monolulu on a flight to Paris, who said that he’d had a Danish passport. He remains keen to find out more.

“Eventually after a lot of research I managed to establish that he was originally from St Croix in the US Virgin Islands,” says Pearson.

“His beginnings were very humble, but he obviously had a very sharp mind and spoke several languages.”

Born Peter Carl McKay in 1881, Monolulu arrived in Britain from the United States around 20 years later, seeking a better life, having earlier claimed to have been shipwrecked.

In London he joined the chorus line of In Dahomey, an all-black West End musical show, and appears to have developed his interest in racing after meeting an Irish tipster.

Away from the track, he could be found in the capital’s markets such as East Street and Petticoat Lane, selling lucky mascots and even medicines that claimed to cure anything from flat feet to baldness.

Pearson has visited St Croix, tracked down archive records and even helped open a new housing development called Monolulu Court in south London.

“There is some myth and legend. If he felt something was going down well, it probably got enhanced a bit. I think a lot of it is true,” he says.

“He says he was married six times, but I’ve only found evidence of three. His claim to be from Ethiopia was a load of rubbish, but it gave him the chance to dress up as someone who would be recognized.

“A black man here in those days had to work twice as hard to make his presence felt in society and Monolulu somehow got right on top of it all.”

Bourne says: “He probably did encounter racism, like many black people would have done.

“There may have been some in the upper classes who laughed at him not with him. The lower classes loved him – he wasn’t a figure of fun, he was a man of the people. If you look at the pictures, he’s surrounded by smiling people.”

Monolulu appeared in newspapers and cartoons and on cigarette cards, and was used by the government for public information campaigns.

As his fame spread, he visited the United States to watch famous boxers such as Joe Louis and Sugar Ray Robinson and appeared alongside the Marx Brothers on television.

He was well known to crime writer Edgar Wallace, racehorse owner Prince Aly Khan and Lord Lonsdale (of boxing belt fame).

“When the Second World War broke out he was one of the first public figures to appear in a newsreel encouraging the British public to carry gas masks,” says Bourne.

“If you go to VE day, he’s in the crowd jumping up and down at Buckingham Palace with a big grin on his face. He bookends the beginning and end of the war. He was a remarkable character.”

Peter Granwe remembers raising a glass to his grandfather when a pub named after him was opened – the Prince Monolulu in London’s Fitzrovia.

His son Cristoffer was with him and has a permanent reminder of his great-grandfather.

“I’m very proud and my son, who’s now 35, is very proud,” says Peter from his home in Sweden. “On his lower arm he has a tattoo of Monolulu, which is from a picture in the National Portrait Gallery.

“I have a small boathouse north of Gothenburg and I have a sort of man cave where Monolulu stuff is all over the wall.

“He was a unique character, absolutely. He liked to make people laugh.”

With Pearson’s help, Peter has researched his grandfather and read his 1950 autobiography in which the list of unlikely jobs is covered.

Read Also: Micah Richards Daniel Sturridge Does Not Deserve Label As Problem Player

“I’m not sure everything in the book is 100%. He made a history about himself,” says Peter, who is a treatment assistant helping young immigrants and drug addicts.

His uncle told him of being carried around the streets of Soho on the shoulders of Monolulu, who would look out for those down on their luck.

“He would give them a piece of paper with his address in Cleveland Street. You can go there, he would say – there is rice and eggs, but you have to do the washing as I have no butler,” Peter says.

“After he died, the place was ransacked. The only thing left in the apartment was lion claws. I got one claw. I gave it to my son for his birthday.”

Comedian and broadcaster Stephen K Amos knows more about Monolulu than most, having narrated a Radio 4 documentary on his life.

“I’m sad his story is not better known,” he says. “I’ve had talks about doing a programme on forgotten black heroes in the UK. He might have to be a four-parter.

“He could have just put his head down, worked in a factory or transport system, and lived a regular life. He chose not to do that in the same way I chose not to do that. If that means taking a risk and it pays off, great.”

Bourne is pleased we are talking about Monolulu in Black History Month.

“He wasn’t a minstrel. He’s a national treasure, no question about it – he was a respected figure,” he says.

“The problem is a younger generation in this country are not told about black Britons in history. It’s the fault of the education system.”

Pearson, who has become friends with members of Monolulu’s family, is still piecing together the puzzle.

“I cannot believe that after so many years I’m still finding out bits and pieces. Things come in from all over the world,” he says.

“It would be nice to have a trust where information could come in. He was such a unique character he would make a fine musical.”

For Amos, he is someone who ‘represented’ – his success earning respect from peers, just as he has with high-profile TV performances such as the Royal Variety Performance.

“To me as a black man, a performer, an entertainer, his story is a part of mine,” reflects the comic.

Read Also: English Open Ronnie Osullivan Beats Brain Ochoiski In Round One

“He’d been through adversity, and made something of himself. Wow, that’s someone to look up to.”

Peter chuckles as he recounts the myriad tales: “The story of my grandfather’s life will never die.”

Monolulu’s story may be a lesson in character and survival. He also leaves a greater legacy.

“It has taught me, if I needed teaching, a tolerance and respect for people, whatever background or colour they are, as long as they are good people,” concludes Pearson.

“He probably cheered a lot of people up, particularly when they were down. He would be very useful in these particular times now.”

Monolulu died on Valentine’s Day, 1965. Legend says he choked in hospital on a chocolate given to him by journalist Jeffrey Bernard.

Not even his grandson Peter or Pearson are sure whether it’s true. A strawberry cream, it’s said, from a box of Black Magic.

It seems too unlikely. But with Prince Monolulu, you just never knew.