An Instagram story posted from a protest over the death of George Floyd was the first sign Naomi Osaka was beginning to find her voice.

After the killing of Floyd, a black man who died when a police officer kneeled on his neck for seven minutes and 46 seconds, Osaka flew to Minneapolis with her boyfriend, the rapper Cordae, to join those demonstrating their anger.

“My heart ached. I felt a call to action. Enough was finally enough,” she later wrote in an article for Esquire magazine.

Since arriving on the tennis scene as one of the world’s brightest talents, the 22-year-old has generally gone about her business quietly and without ever appearing to be all that comfortable in the limelight.

The softly spoken Japanese player has described herself as the “most awkward”

person in tennis and gave what she said was the “worst acceptance speech of all-time” after winning the 2018 Indian Wells title.

Most onlookers were won over – that speech was an endearing, giggly and self-deprecating monologue, one of the best – but Osaka has rarely seemed at ease speaking in front of large crowds. At news conferences she would often shuffle uncomfortably in her seat before giving short answers or making references to Pokemon.

That does not mean there was not a powerful voice inside the three-time Grand Slam champion, who won the US Open for a second time on Saturday.

Osaka was born to a Japanese mother, Tamaki, and Haitian father, Leonard, in the city with which she shares her surname, before the family moved to New York when she was three years old.

In her Esquire article, she discussed how her multicultural background has led to “people struggling to define” her.

“I’m a daughter, a sister, a friend and a girlfriend. I’m Asian, I’m black and I’m female. I’m as normal a 22-year-old as anyone, except I happen to be good at tennis. I’ve accepted myself as just me: Naomi Osaka,” she wrote.

Another label which has been attached to her in recent months is: activist.

On the eve of the US Open, Osaka pulled out of her Western and Southern Open semi-final in protest at the shooting of Jacob Blake, a black man, by police in Wisconsin.

Her move, joining other protests by American sports stars, prompted the entire tournament to “pause” for the day.

“Before I am an athlete, I am a black woman,” Osaka said. “And as a black woman I feel as though there are much more important matters at hand that need immediate attention, rather than watching me play tennis.”

Osaka decided to play the following day when the event resumed. While she says she is “more of a follower”, her actions were decisive and commanding.

“I was waiting and waiting and then I realized I was the one who was going to have to take the first step,” she said.

“I just wanted to create awareness in the tennis bubble. I think I did my job, I guess.”

On the sport’s biggest platform – a Grand Slam event, even one behind closed doors – her fight against racial injustice and police brutality continued.

Before and after every US Open match she wore a face mask bearing the name of an African-American person killed.

Breonna Taylor. Elijah McClain. Ahmaud Arbery. Trayvon Martin. George Floyd. Philando Castile. Tamir Rice.

Each match she won before Saturday’s final meant another chance to display a name. Her coach, Wim Fissette, said it provided her with the extra motivation to succeed.

“It’s definitely helping her and giving her more energy,” said the Belgian.

“She wants to be a role model off court and knows it has to go with being a role model on court. It is a good combination.”

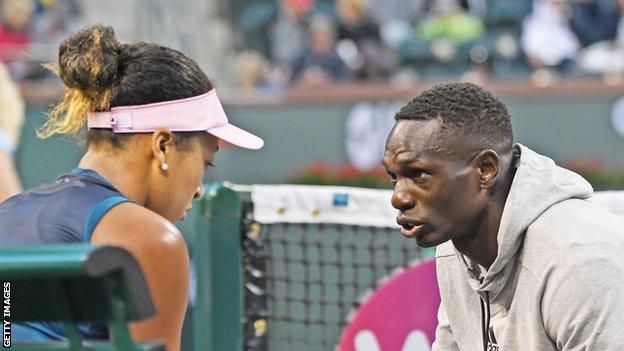

Fissette became Osaka’s coach in December, replacing American Jermaine Jenkins.

Last summer, Osaka, Jenkins and the rest of her team were in the United Kingdom for the grass-court season and preparing for a Women’s Tennis Association tournament in Birmingham.

Together, they watched a Netflix series called When They See Us. The drama is based on the true story of five black, male teenagers from Harlem falsely accused of a brutal sexual attack in New York’s Central Park.

Jenkins believes that was a pivotal moment in Osaka realizing she could use her voice more.

“I feel that gave Naomi, and everyone, a different view and perspective on how black men in America are treated,” said the now national coach at the United States Tennis Association.

“I feel that really touched her heart. No-one can really watch that without crying. It made her really sad and we discussed it, had a conversation about it and it makes me proud to see her come out and be the advocate that she is.

“I met her at a time when she was still in a cocoon a little bit, right at the birth of her blossom in coming out and having a voice. You could see she was still maturing in that department. Now I feel she’s at that next stage.

Read Also: Merih Demiral Leicester End Interest In Juventus Defender After ACL Injury

“As a black man in America it is empowering and makes me feel great she is stepping up, taking the heat and standing up for what, in my opinion, is right. This is now her platform.

“She doesn’t have to do it, she can easily stay quiet. I think it is brave and it makes me feel good inside.”

Osaka using her platform as one of the world’s biggest sports stars is not only raising awareness among fans, it is also making her fellow players take note.

Greek world number six Stefanos Tsitsipas was shown wearing a Black Lives Matter T-shirt during the US Open, with Osaka saying she was “super proud” of her friend for asking more questions about racial inequality.

When announcing she would not play at the Western and Southern Open, Osaka said the aim of her actions was to “get a conversation started in a majority white sport”.

Many within the confines of tennis will not have an understanding of the racism suffered by black people.

To prove the point, even one of Osaka’s former coaches, Sascha Bajin, was widely criticized for a social media post after Floyd’s death where he said “colour isn’t an issue” in Europe.

Jenkins says being a black person in tennis can lead to a feeling of isolation and not being part of “the in crowd”.

Even though there are several prominent black players – for example, the Williams sisters, Sloane Stephens, Coco Gauff, Gael Monfils and Frances Tiafoe – there are few black administrators, coaches, agents or members of the media.

American Tiafoe, who reached the last 16 at the US Open, said watching Osaka use her platform to highlight racial injustice has been “special”.

“I bet a lot of people weren’t for that, but she believed in something. She’s coming out with a different mask every night. She’s trending. She definitely figured out, she’s definitely woke,” said the 22-year-old, who also wore a Black Lives Matters mask and hoodie before his matches.

“I’m proud of her and I keep hoping she’s doing the same thing.

“I’m going to try to do my things on my front. Sloane is too. I know the Williams sisters are. All these guys. I’m just happy to be a part of that list.”

Osaka, though, has a unique reach across the world because of her Japanese, Haitian and American heritage.

In her Esquire article, she also wrote about how tackling racism in Japan can be “challenging”. Osaka herself was “whitewashed” in a cartoon advert by one of her sponsors in the country last year.

While her protests have largely been centered around American events, she hopes to use the global platform of tennis to shine a light on more social injustice.

“I feel like definitely that would be the end goal, because tennis is an international event. It’s played by so many people around the world,” Osaka said this week.

“I feel like there is always a very good opportunity to speak out about subjects. I feel like as soon as one player starts talking about it, then it kind of opens the door for everyone else.”

Tennis is crying out for new, globally recognized faces to carry the sport forward, and for new leaders to emerge. The golden generation – fronted by Serena Williams, Venus Williams, Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic and Andy Murray – is heading towards retirement.

Last year, Osaka struggled to deal with the pressure of being a leader and being the world number one.

After losing in the French Open third round last year, she said it was “probably the best thing which could have happened” and revealed she had been suffering from headaches because of the “stress” of being the top seed.

Before defending her Australian Open title in January, she talked about how she still found it difficult being described as a “top player”. Handling the increased scrutiny was “tough”, she said.

This fortnight at the US Open, Osaka has demonstrated her growing maturity and how she has learned to cope. Exuding confidence on and off court, she has believed in her game and believed in her principles. Marrying them together has led to an unbeaten run of 11 matches since the sport returned, culminating in a third Grand Slam title.

Though undoubtedly already a superstar, she appears to be moulding into a natural heir to the ageing icons. Talent on the court is what initially told the world she was special – now her actions and words are marking her out as an emerging leader with the power to inspire.

Jenkins agrees: “She is the future of the sport. And she’s doing it now.”